I was stuck so badly that the ominous python of fear started uncoiling in my stomach, threatening to bring on panic that would fuddle all rationale. I was in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument area, a 2,656-square-mile expanse of canyonlands with minimal infrastructure – a waterless region so inhospitable that it was the last to be mapped in the continental US.

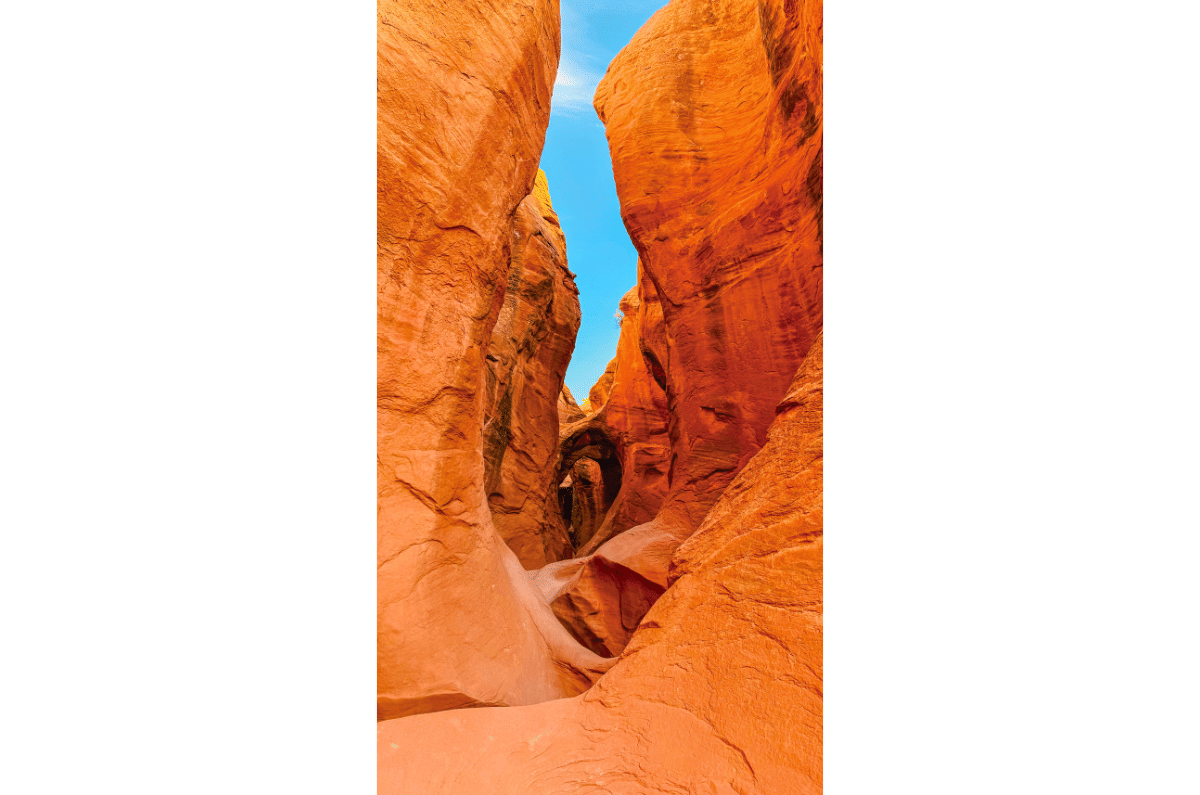

Somewhere in the middle of nowhere in this vast area ominously called the Badlands, I was jammed in a dark canyon while trying to squeeze through wafer-thin clearances of rock. Boulders that had fallen into the canyon had blocked my way, and the only option was to wriggle into the hole under them and exit and crawl up on the other side. A ‘U’ bend that I had to negotiate head first, crawling on my stomach.

And at the very apex of the ‘U’, I got stuck. I was woefully wedged like a renegade particle of sand not fine enough to pass through the neck of an hourglass. A menacing mix of doom and claustrophobia started to cloud my mind. A week ago, on a Sunday in October ’24, I had landed in Los Angeles, resplendent with its wide boulevards, on an invitation from Royal Enfield to experience the new Bear 650 – the latest iteration based on their very popular 650cc twin-cylinder engine.

Unfortunately, forest fires raging near Big Bear Lake meant that the media event had to be postponed by 10 days. I spent my first three days exploring California’s most eclectic city, where America’s richest and poorest, the most refined and the roughest share graffitied streets with starlets seeking fame and fortune. The city’s vibrancy vaporised my jet lag in a jiffy.

Based at the Hoxton Hotel in downtown LA (DTLA), I easily surpassed my daily goal of 10,000 steps exploring Los Angeles’ neighbourhoods. In the Vinyl District, the revitalised neighbourhood that celebrates the city’s music industry past, I had a smashing meal at Mother Wolf, an Italian restaurant that is chef Evan Funke’s homage to the Eternal City and culinary heritage of La Cucina Romana.

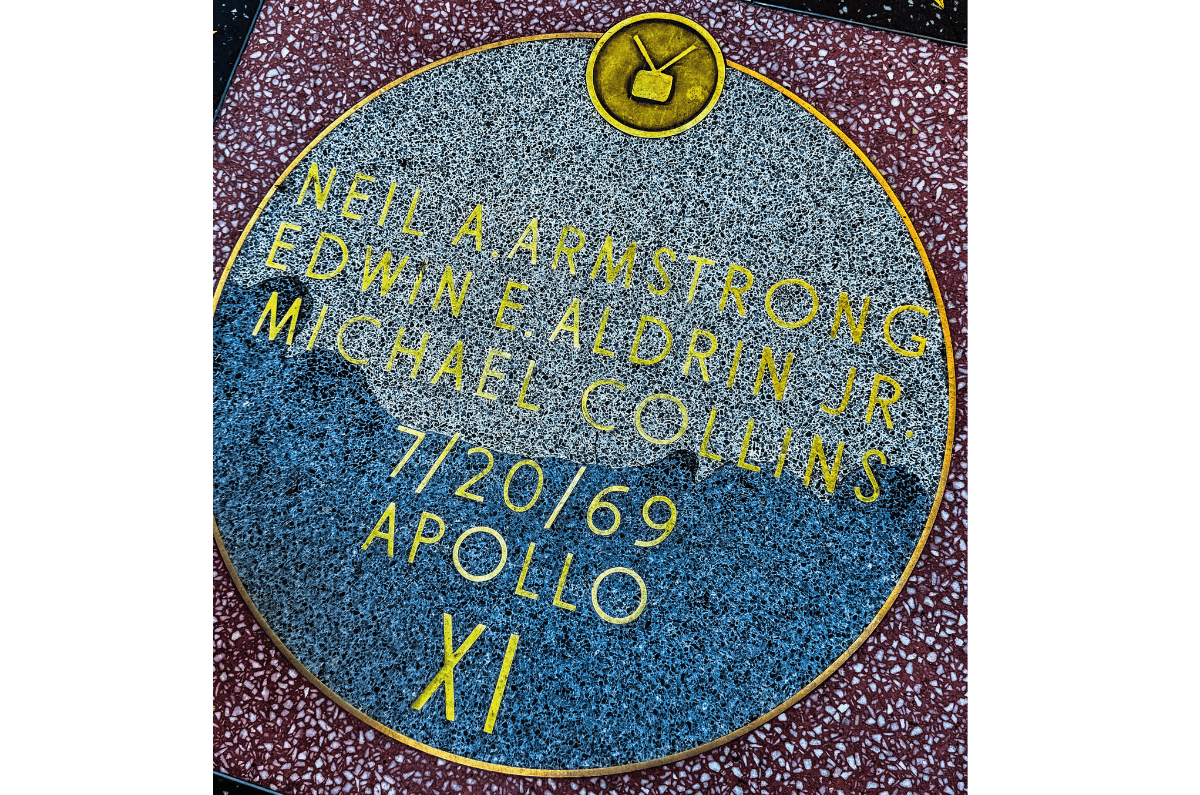

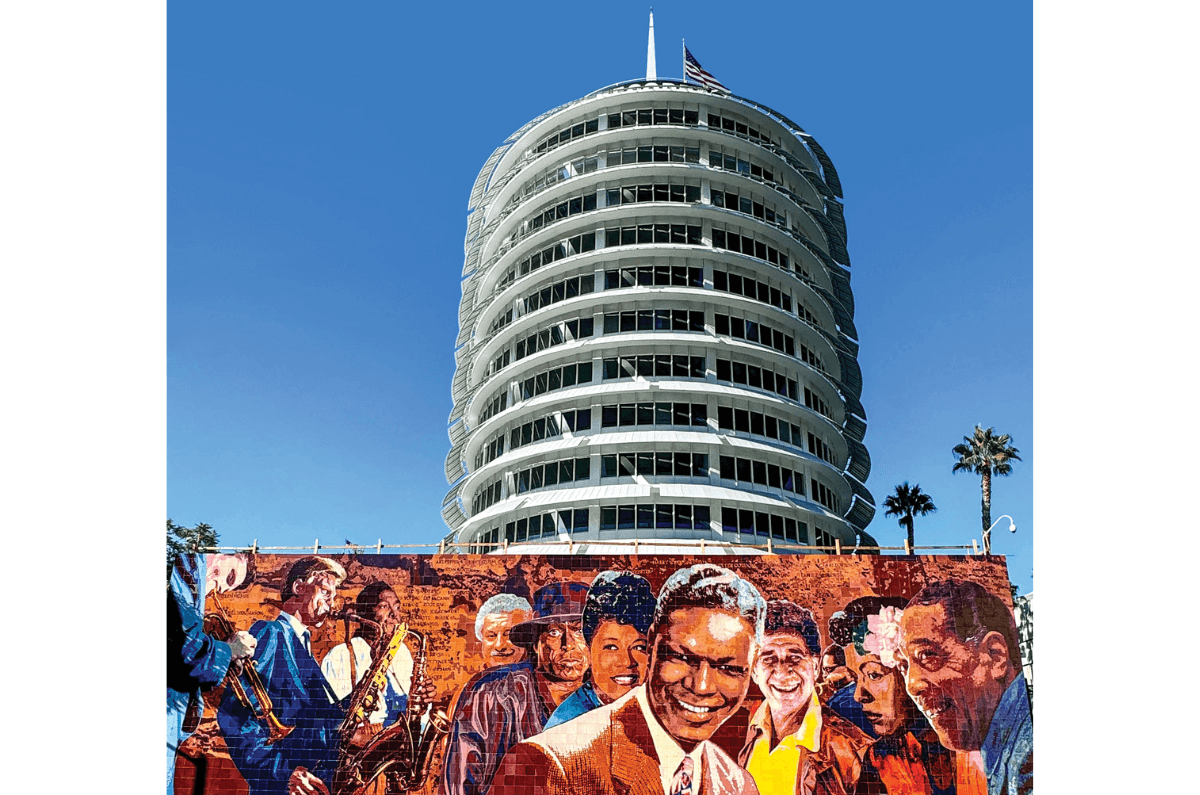

Ambling down the famous Walk of Fame, amongst bronze stars celebrating Hollywood greats, I spotted the commemorative dedications that mark the Apollo 11 mission at the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street. A three-minute walk up Vine Street from there, I marvelled at the 13-storey Capitol Records building that resembles a stack of vinyl records on a turntable. It was designed by Louis Naidorf of Welton Becket Associates and built in 1955.

Today, it is an LA landmark, as is The Last Bookstore on Spring Street in DTLA. The dramatic name notwithstanding, it is the largest new and used bookstore in California, spread over 22,000 square feet. They have tonnes of books, comics, vinyl records and little nooks and crannies to hide away from the world and get lost in a book. They also have vaults, and there is a rumour that there are ghosts wandering about, too. For a person interested in the written word, this is a wonderland.

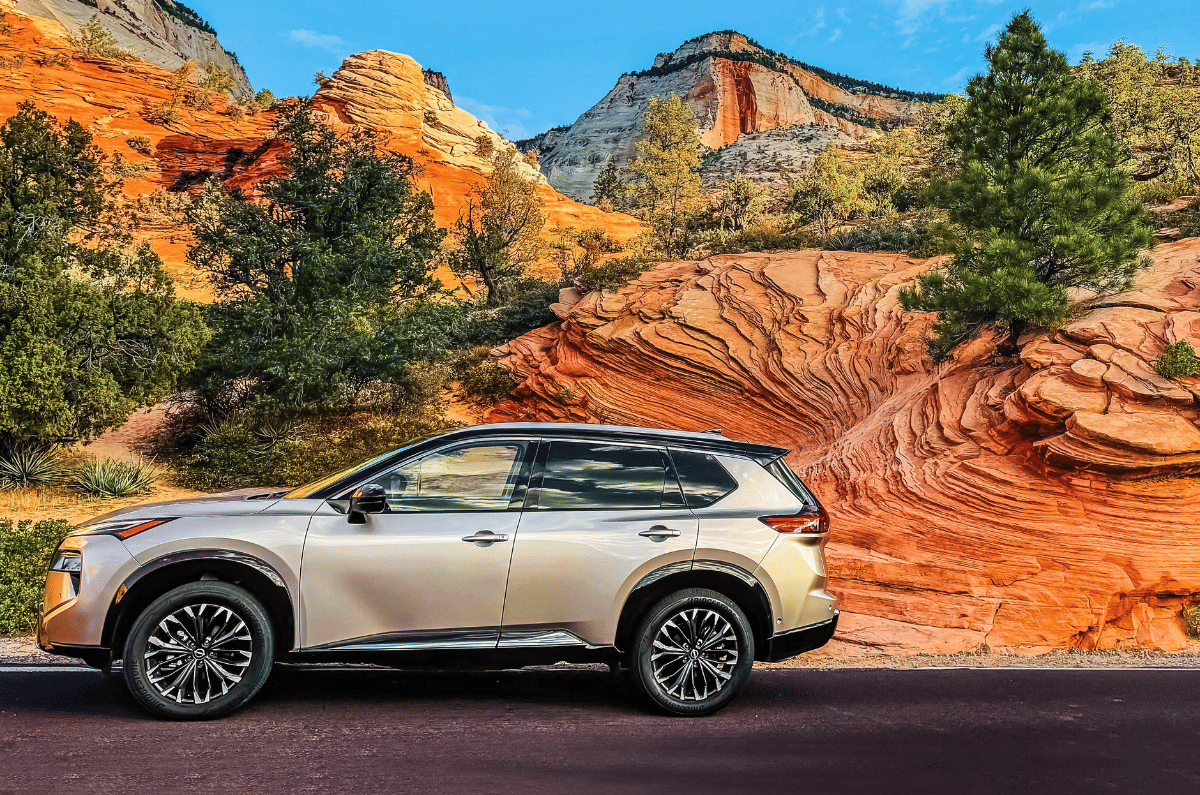

More varied and delicious food happened at the vibrant District Market. I walked in ravenous at the South Hill Street entrance and left stuffed and satisfied from the Broadway exit. On the fourth day since my arrival, I started itching to head out into America’s wide-open spaces, so I headed northeast on Interstate 15 (I-15) from LA at the wheel of a 2024 Champagne Silver Nissan Rogue Platinum AWD. My plan was to head to Zion National Park, 423 miles away.

Even before Los Angeles had completely faded away in my rearview mirror, I realised that the Rogue was quite the gentleman’s butler on this wide and fast interstate with varying traffic volumes. The adaptive cruise control and lane assist kept speed and symmetry tidy in relation to traffic around me. My phone wirelessly shook hands with the BOSE premium sound system via Apple CarPlay, and the music flowed sweetly out of the 10 speakers. I distinctly remember driving past Las Vegas while Dvorak Symphony No. 9 – From the New World – thundered in the Rogue; I couldn’t help but think that for pure sound and acoustic design, the Rogue would rival many of the concert venues in Sin City.

The 12.3-inch multifunction information display presented Google Maps so bright and big that there was no lag in my 52-year-old eyes to adjust from myopia to hyperopia.

I made it to the Econo Lodge at St. George in Utah, which is about 40 miles short of the south entrance to the Zion National Park. The Nissan delivered 33mpg (14kpl), which is quite on point compared to its spec-sheet figure of 34mpg. Of course, the credit for this goes to its electronic brain rather than my boot because I was on cruise control most of the way.

Zion was crowded like the Sassoon Docks in Mumbai is when the heavily loaded fishing trawlers come in.

Even though I was on the road at 4.30 am, when I got to Zion National Park’s south entrance an hour later, there was already a backlog of cars waiting to get in. It took another 45 minutes before I drove to the ticket window and entered the park.

Zion’s iconic sites and sights that make it to documentaries, travel magazines and tourist brochures – the Temple of Sinawava, the Court of the Patriarchs, the Emerald Pools and the Narrows, to name a few – are on the Zion Canyon Road. This road is closed to private cars and only serviced by park shuttles to better manage the sheer volume of visitors. To put a number to these words, Zion NP welcomed 5,17,501 visitors in October 2024 and 49,46,592 of them through the last year.

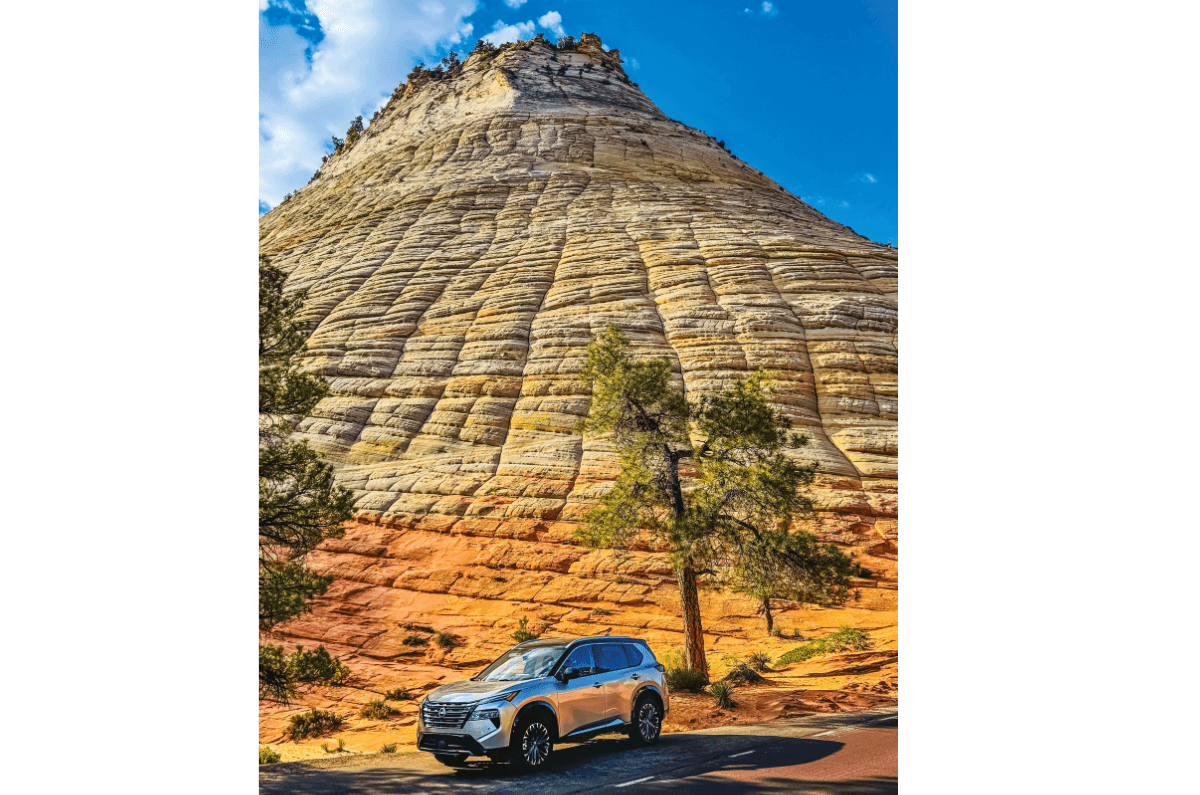

The sun wasn’t up yet, and already, there was a serpentine queue of people waiting to board the shuttle to Zion Canyon Road. It was just too many people for me too early in the morning, so I gave that a miss and carried on through the national park on the Zion-Mount Carmel Highway. I stopped at a few places to get some photos – the most noteworthy being the Checkerboard Mesa. But Zion just didn’t call out to me, which was disappointing because it had been on my list of places to visit in the US for many years.

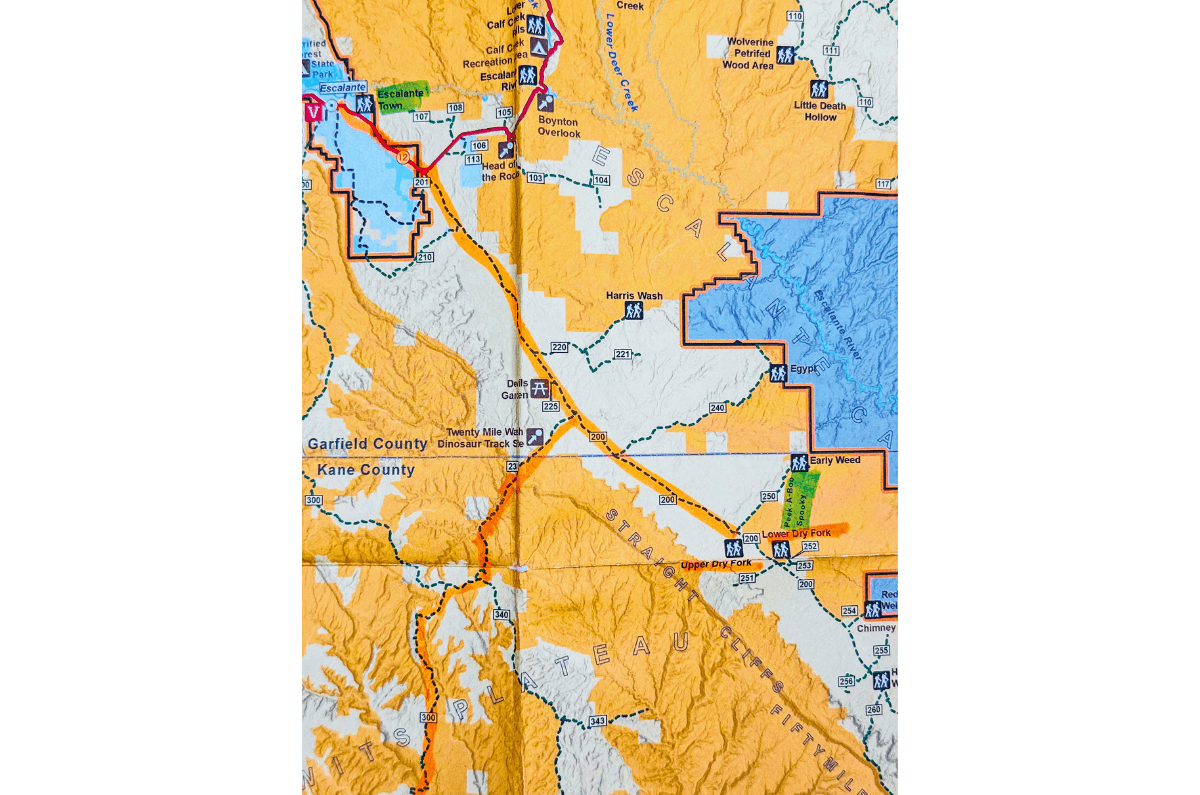

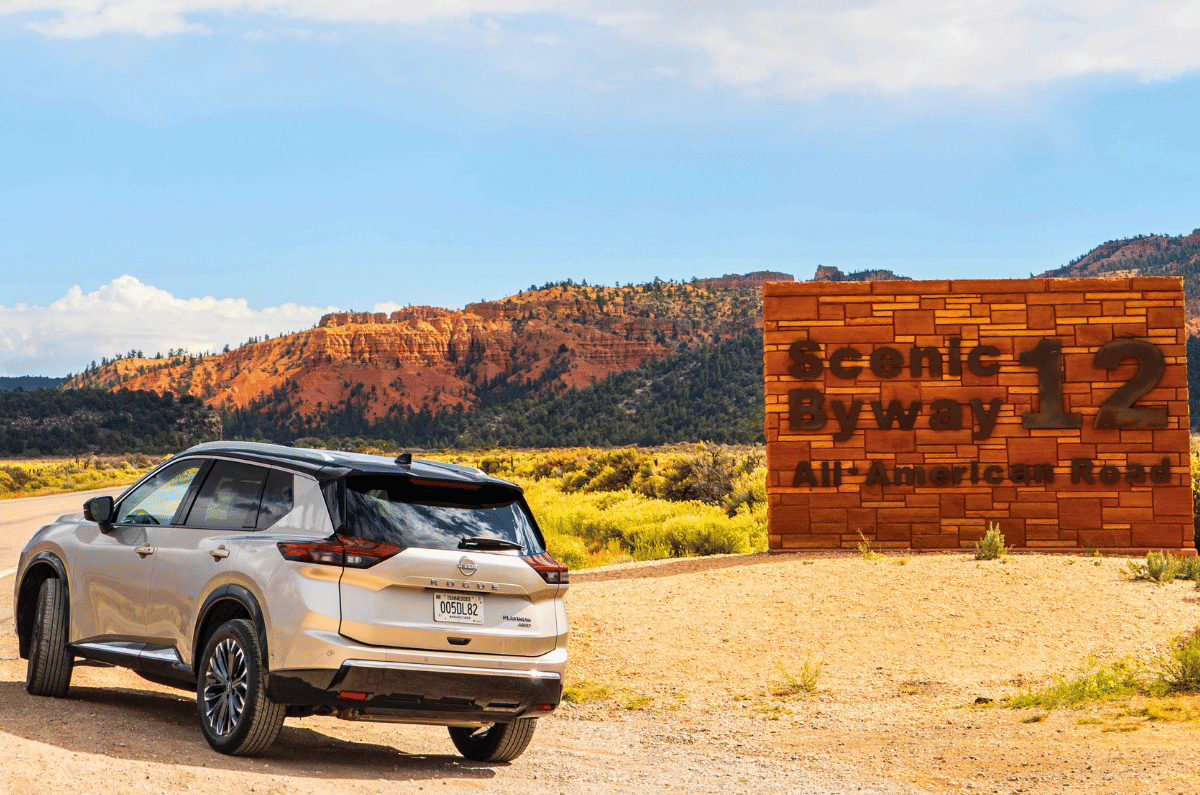

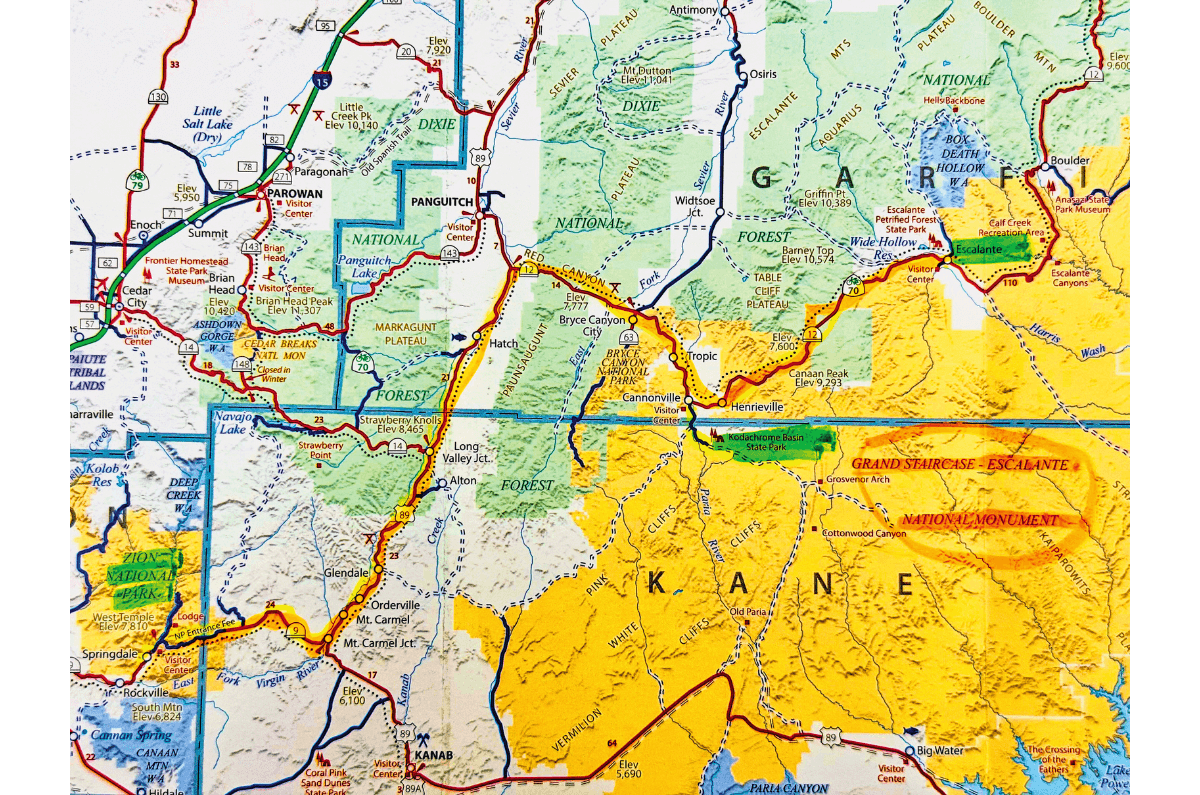

I pulled over and spread out a large-scale Utah map on the bonnet of the Rogue and planned my next move. Sitting to the east of Zion, the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM) caught my eye. The park ranger I spoke to at Zion’s East Entrance Ranger Station told me that GSENM sees very few tourists and is mostly deserted, which is exactly what I was looking for. So, I decided to head up US-89 and then take Utah Highway 12 (UT-12) to Escalante.

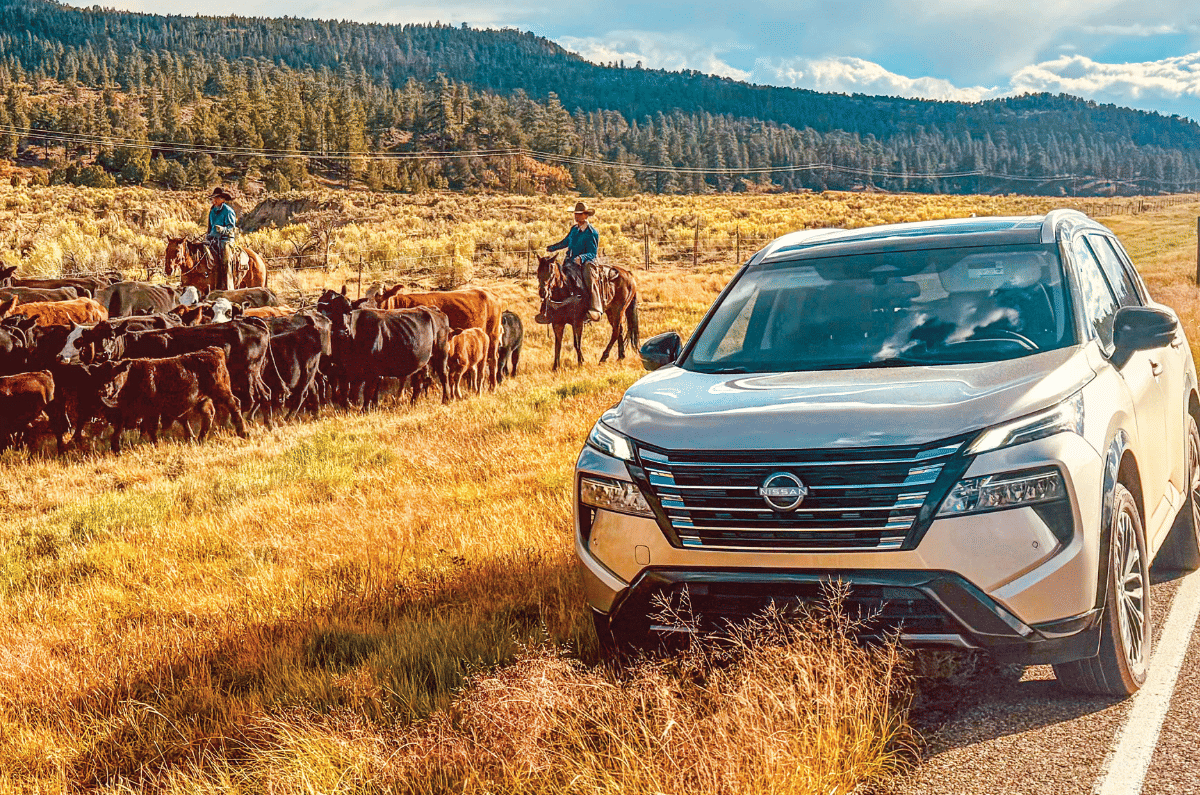

Called the Scenic Byway 12 All-American Road, the UT-12 is arguably Utah’s most diverse and stunning route. It winds through rugged canyonlands on a 124-mile journey west of Bryce Canyon to near Capitol Reef. On this road, with just a little bit of imagination, you can envision how it must have been during the westward expansion era of the nineteenth century, with wagons making their way on rough-hewed tracks through a moonscape of sculpted slickrock and crossing over narrow ridgebacks. In fact, I even came across horse-mounted cowboys herding cattle, complete with leather chaps and Stetsons.

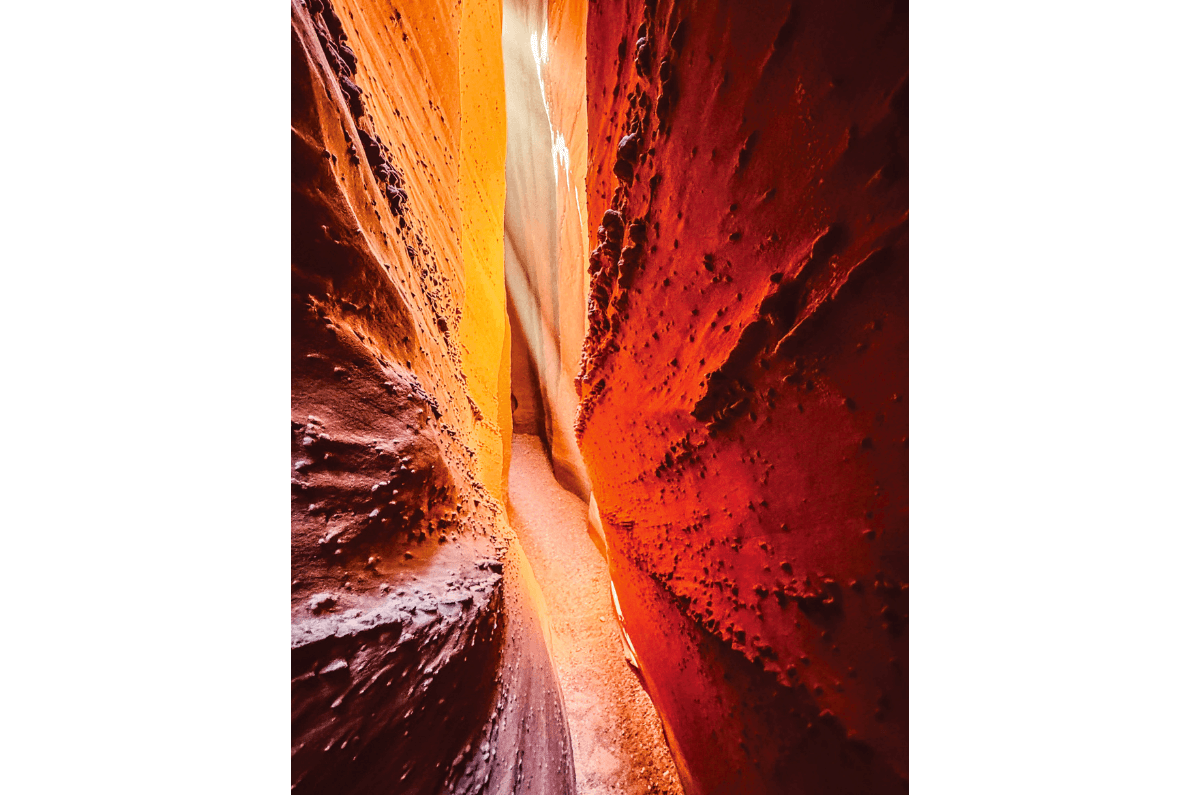

On the way to Escalante, at Cannonville, I detoured to the Kodachrome Basin State Park and drove to the Willis Creek trailhead. This is a 4.5-mile trail that goes through a slot canyon at some places. Wikipedia describes a slot canyon as “a long, narrow channel or drainageway with sheer rock walls that are typically eroded into either sandstone or other sedimentary rock. A slot canyon has depth-to-width ratios that typically exceed 10:1 over most of its length and can approach 100:1”.

The slot canyon I walked through on the Willis Creek trail was easily wide enough to ride a motorcycle through. Unfortunately, the gauge of this slot canyon set a standard for slot canyons in my mind. It was a very bad error of generalisation. Driving further east on UT-12, I arrived at Escalante 41 miles later and pulled into the Prospector Inn, where I shacked up for the night.

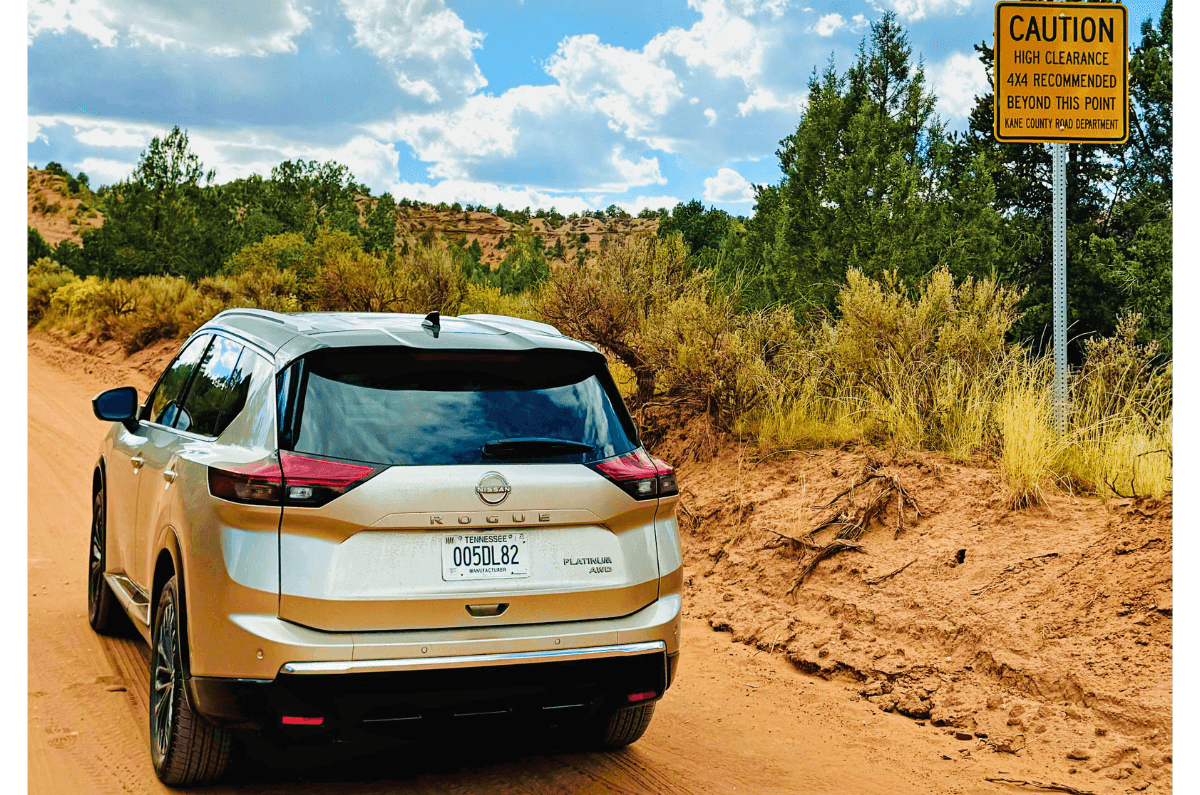

The next morning, while I was grabbing a coffee at Destination Café across the road from the Prospector Inn, the chirpy barista told me that while she was new to this region, she’d heard that the Peek-a-Boo and Spooky Gulch slot canyons are pretty interesting and exciting. She said she had yet to get out there and explore them, though. This should have warned me that she had no firsthand experience, but I was still equating slot canyons to the breadth of the one that I had walked through at Willis Creek the day before. Instead, I should have read up about these particular canyons before attempting to traverse them. That was my first mistake. Besides that, the road out to the trailhead was an absolute dirt track, and this was further bait for me since I was itching to get off the tarmac and make some mischief with the all-wheel-drive and high-ground-clearance Rogue.

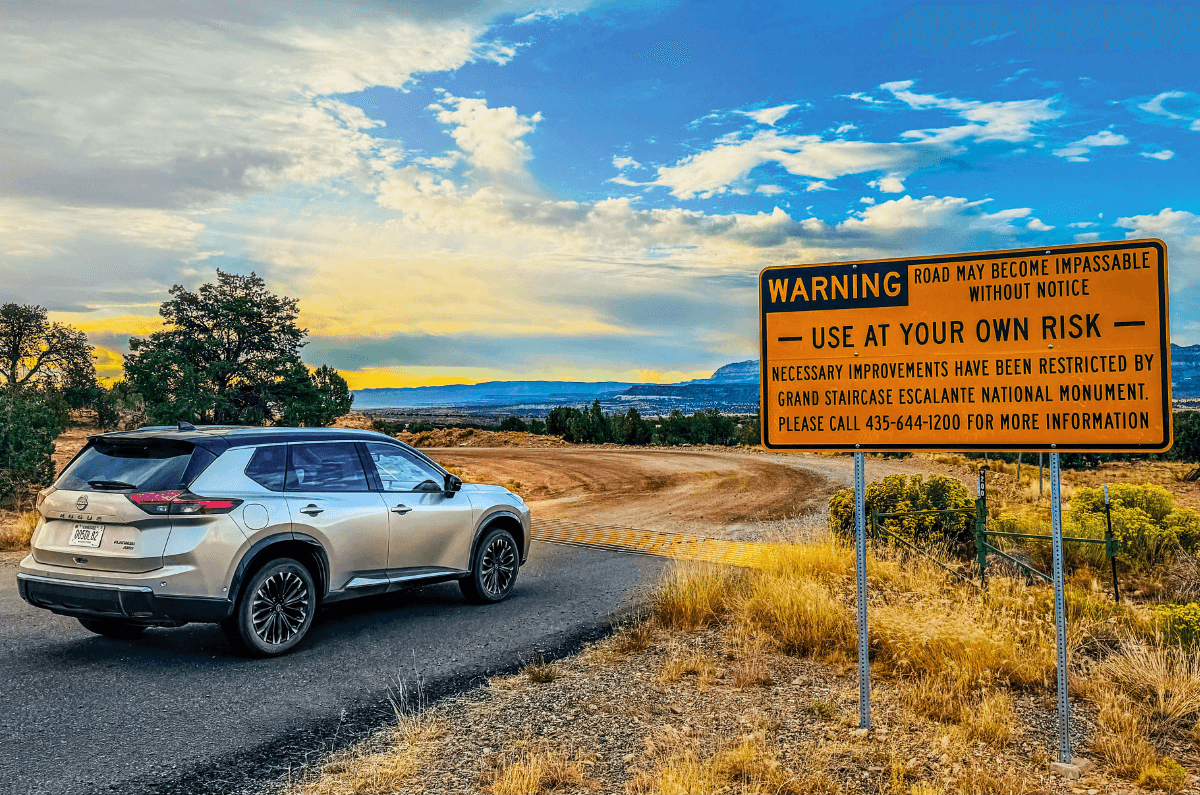

I put on my hiking boots and headed out west on UT-12 for 5.4 miles, after which I turned right onto a dirt track demarcated as BLM (Bureau of Land Management) 200, also known as Hole-in-the-Rock Road. I casually dismissed the large warning sign here since the sky was blue, and the weather forecast said it would continue to be so.

The Rogue was absolutely at home on the 30 miles of dirt that followed to the Upper Dry Fork Trailhead parking lot. Even hard cornering over loose gravel didn’t make it throw its rear out. However, on the stretches where ‘washboarding’ had occurred, the Nissan did not provide a particularly pleasant or pliant ride. Upping the speed smoothened things out a bit, but that made me uneasy because there were sudden and deep dips on this road.

When I arrived at the Upper Dry Fork parking lot, which is one of the trailheads, I completely missed

seeing the sombre warning sign mounted on two parallel steel supports. It clearly states that anyone who struggles to fit their body through the gap between the supports should not proceed through Spooky Gulch. Missing that warning sign was my second mistake.

Unlike Zion, this region was absolutely deserted, and even the foot trail was very faint. Thankfully, there were cairns (small rock towers arranged by hikers to serve as markers) at regular intervals to show me the way. Plus, I had downloaded the trail on my AllTrails app, and that, too, helped me along.

When I arrived at Peek-a-Boo, the entrance was approximately 15 feet high up a slickrock wall that required climbing to access the canyon. It had shallow footholds, and I saw two hikers shimmy up it, but it proved quite a challenge for me. As I struggled to hoist myself up the smooth wall, a woman behind me, waiting to climb into the canyon, put her shoulder to my posterior and gave me a much-needed boost. She cheerfully called out an apology for taking the liberty to do so once I had clambered into the canyon. I waved back to her, grinning with gratitude, telling her that I, too, believed in the principle that it is better to ask for forgiveness than for permission!

Peek-a-Boo Canyon was an all-out callisthenics workout with climbs and drops that had me calling upon some muscles that had been dormant for a while. But this canyon was 3 feet wide at its narrowest – so, in theory, still broad enough to ride through with a Royal Enfield Himalayan, which is 2.7 feet wide. I was feeling quite a sense of achievement as I exited Peek-a-Boo Canyon and walked the half mile to Spooky Gulch, but my euphoria completely evaporated within 10 minutes of entering it. I had spent more time walking sideways, scraping my chest and back on the red and purple sandstone that seemed to very grudgingly let me through. Apprehension fuelled by watching the Indiana Jones movies too often brought on an irrational fear that the walls might start closing in.

Besides that, there was no turning back because I could hear people behind me, and I could literally not turn my head because my ears were brushing the walls. I shuffled on, hoping that the canyon would widen out, but it stayed narrow as ever, the gap akin to a serpent slithering along. And because of its curvaceous nature and my restricted turn of head, I couldn’t tell what lay around the next bend. At times, my wide US-13 size hiking boots got wedged between the bulges of rock at the floor, and getting them free was akin to making a 6-point U-turn on a 9-foot-wide mountain road.

Just when I thought it couldn’t get any more challenging, I came to the boulder fall that I started this narrative with.I first tried to clamber over the boulder, which was like going up a chimney. But when I reached the top, I was dismayed to see that it was a long and sheer drop off the other side. So, I had to shimmy down the same side of the boulder. The only option was to cross from under the boulder, which meant descending headfirst into a small dark hole, and right when I was under the boulder, I got stuck. The very thought of being stuck under tonnes of rock mentally took me almost over the edge of reason and into the threatening abyss of hysteria. But I gathered my wits, took a moment to assess my movement ability and realised that I could bend my knees a bit.

Using my knees and the toecaps of my boots for traction, I inched ahead till I could once again use my hands to propel me forward. Inch by inch, I managed to clear the rock and crawled out on the other side. To my horror, the canyon was now no more than a 10-inch crack splitting the sandstone, and to add to the shock, I could hear voices up ahead. There were people coming the other way. They’d heard me, too, and had considerately waited at a point where the path bulged to 20 inches across. They were locals who had traversed this canyon before, and I think my traumatised expression seemed to suggest that I was begging for reassurance that the worst was behind me.

A portly gentleman took pity on me and said, “You’re not out of the woods yet, and there is a technical section up ahead!” “But”, he added, patting his expansive belly, “I made it through, and so will you,” he guffawed. Thankful and reassured, I carried on and came up to the section he had referred to. It was a 20-metre stretch in the shape of a crescent moon, where the gap through the rock was no more than 10 inches wide. The fit was so tight that when I was halfway through, I got stuck again, and I had to shuffle back and remove my wallet from the rear pocket of my trousers to go through. I don’t think I have ever been so grateful in recent times as I was when I walked out of Spooky Gulch.

I had started my trek early in the day, and the few people I had encountered, save for the portly man and gang, were doing the trail loop in the same direction as me. But when I exited the canyon and started the 2-mile walk back to my Nissan, I saw a number of people going the other way. I shuddered once again, thinking of the chaos that would ensue when people going in opposing directions met at the terrifyingly narrow sections.

I was euphoric at making it through Spooky Canyon, but my jubilance was short-lived because when I got back to my car, I looked up this trail online. I was aghast to read that in 2021, a 52-year-old man had gotten stuck in Spooky Canyon for nine hours before he was rescued, and, in 2017, a 62-year-old hiker from Alabama had died of thirst and exhaustion on the trail after going halfway through Spooky Canyon and then turning back. I am not lithe and fit, and I have never been canyoning before, and I realised how incredibly lucky I had been.

Buoyed by the fact that I was done with slot canyons and the weather forecast was clear, I forsook the tarmac and took the 70-mile BLM roads through the GSENM. There were some very torturous sections with deep sand traps, but as long as the sky was above me and wide open spaces around me, I was at ease, trusting the Rogue completely.

My plan was to drive south into Arizona to visit a friend in Phoenix before heading back to Los Angeles. On that day, I stopped for the night at Page, which is the staging point for Navajo-led tours into the Antelope Canyon, one of the most visited slot canyons in the Southwest. Since it is on tribal land, it can only be visited on a tour led by a Navajo guide. They have special photography tours, too, where enthusiasts set up tripods to get that perfect long-exposure shot. So, obviously, Antelope Canyon is quite roomy.

Yet, when my waitress at dinner that night asked if I was headed to Antelope Canyon, I said no so forcefully that she took a step back in shock. For all I care, Antelope Canyon could be a wonder of the world, but for the moment, I was done with slot canyons!